Twenty Pearls Installation View, Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto, 2010

Butterfly Skull

collage of cut images from used books sewn together with thread,

47 x 28 inches

2010

Nest Skull

collage of cut images from used books sewn together with thread

30 x 26 inches

2010

Gold Skull

collage of cut images from used books sewn together with thread

43 x 31 inches

2010

Gem Skull

collage of cut images from used books sewn together with thread

42 x 24 inches

2010

Black Bird Skull

collage of cut images from used books sewn together with thread

46 x 28 inches

2010

Finch

collage of cut images from used books sewn together with thread

77 x 68 inches

2010

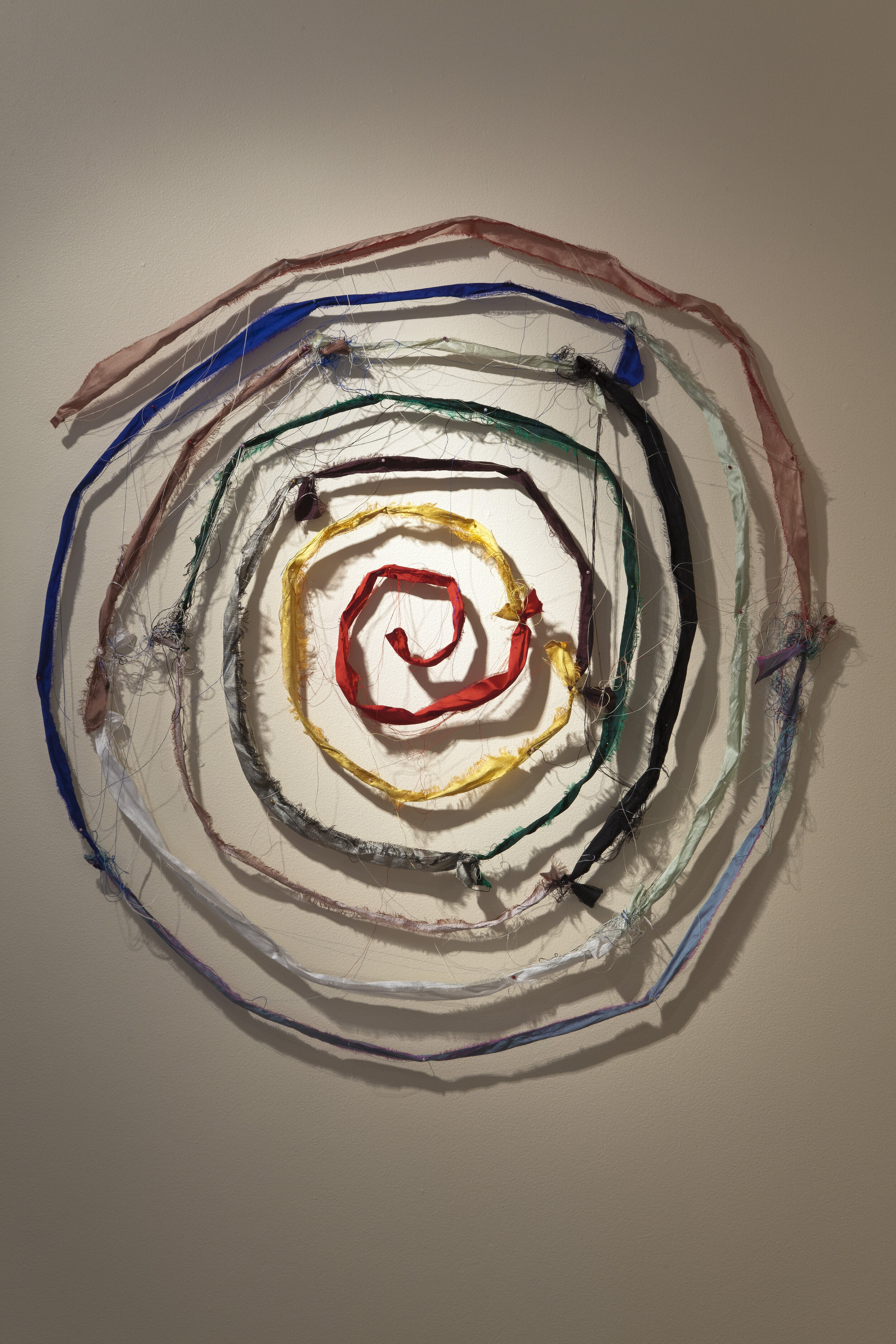

Silk Spira

torn and knotted silk

2010

Gold and Black Eyes

gold leaf and silk velvet

2010

Munari’s Eyes

satin cord

2010

North, South, East, West

coloured and mirrored Mylar on paper

2010

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

R.M. VAUGHAN: THE EXHIBITIONIST

Jennifer Murphy's sculpture-collages weave a hypnotic web

R.M. VAUGHAN

SPECIAL TO THE GLOBE AND MAIL

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 24, 2010

Jennifer Murphy at Clint Roenisch Gallery Until Oct. 9, 944 Queen St. W., Toronto; www.clintroenisch.com

Contrary to the stereotype, most artists are industrious sorts. And then there's Jennifer Murphy - the one-woman sweatshop.

Twenty Pearls, Murphy's fantastic new set of sculpture-collages at Clint Roenisch Gallery, combine fragility and bombast, the delicate and the spectacular, with unnerving skill (and seemingly limitless patience).

I'm not a big supporter of the Protestant work ethic as a value in itself, but when a work of art is so obviously labour-intensive and yet made to look effortless, even slight or ephemeral, one can't help but shake one's head in amazement and admiration. Murphy weaves hypnotic webs.

Here's her process: combing through old encyclopedias, art books and magazines, Murphy cuts out images of animals, plants, insects, gems, birds, skulls … whatever grabs her eye.

She does not, her gallerist assured me, print images off the Internet: The quality of the printed image thus sourced is simply not good enough.

From this collection, Murphy hand-sews bits together to make large, abstract constructions (in this case, the bulk of the works resemble skulls) - works big enough to fill a bathtub, but so frail they can only be held up with sewing pins.

Murphy's puzzle-fitting is deft, a marvel to watch. The sizes, shapes and colours of her culled sources cohere neatly, with strong internal composition, and are thematically intriguing. For instance, one of her skulls is composed of cutouts of jewellery and gemstones (a Damien Hirst nod?), another from cutouts of mummified heads and early-human skulls. My favourite skull was made with cut-outs of black-furred, feathered and scaled animals.

In The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience, a defence of ornament and kitsch, Celeste Olalquiaga describes the 19th-century habit of turning "the novel world of industrialized production [into something]more familiar by shaping it after plants and animals," a penchant that created "organic and mechanical … wish images" (such as wrought-iron lamps made to look like flowering plants).

Murphy's works update this material culture anxiety by trading the 19th-century uncertainty over mechanized production for our current unease with instant, and continuous, image production.

But you hardly need consider all the cultural ramifications of Murphy's beautifully layered artifices, her simulacra leap-frog games, to enjoy the final products. If anything, you'll be too busy propping up your jaw.

Canadian Art

MARCH 15, 2011

Jennifer Murphy

Toronto, Clint Roenisch

Spread from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art

by Bill Clarke

Using the word “collage” to describe Jennifer Murphy’s work oversimplifies it. While the cutting and arranging of images plays a large part in Murphy’s process, she eschews the traditional pictures-on paper approach to collage by installing her constructions directly onto gallery walls. “Twenty Pearls,” Murphy’s first exhibition at Clint Roenisch, demonstrated that her practice has evolved; she handles her materials with a sculptural approach.

The selection of imagery is left to chance. Murphy culls the components for her collages from science and nature textbooks found at yard sales, used book stores and thrift shops, and from magazines like National Geographic. In this exhibition, Murphy used colourful images of birds, animals, insects, gemstones and flowers to construct a suite of five works that, from a distance, resembled skulls. In Black Bird Skull (all works 2010), the outline of a skull is delineated by rows of birds perched on tree branches. Butterfly Skull’s hollow nasal cavity is represented by a large moth, and its eye sockets are a pair of cells. The jewel-laden baubles that make up Gem Skull recall For the Love of God, the infamous diamond-encrusted skull that Damien Hirst produced in 2007. Gold Skull is made up almost entirely of pictures of smaller skulls and mummified heads, which suggests the work of photographer Jack Burman (who is also represented by the gallery). Each of Murphy’s skulls includes 50 or more individual pieces deftly stitched together with thread. She floats the assemblages away from the gallery walls with long straight pins, which gives them a web-like, sculptural aspect. Hanging away from the walls, the works quiver gently with the circulation of air.

The centrepiece of the exhibition was a large silhouette of a finch comprised of almost 100 individual images of birds, bugs, snakes, cats and gemstones. Displayed against a wall painted in eye-popping canary yellow, the piece sounded an optimistic note in contrast to the more elegiac skulls. In the end, Murphy comes across as an artful naturalist. She reminds viewers that everything in this world— the precious and the commonplace, predators and prey, the living and the dying—coexist in a delicate, interconnected balance.

This is an article from the Spring 2011 issue of Canadian Art. To read more from this issue, please visit its table of contents.

Bill Clarke